A telescope on a Boeing 747 has for the first time collected evidence that molecular water exists on our satellite.

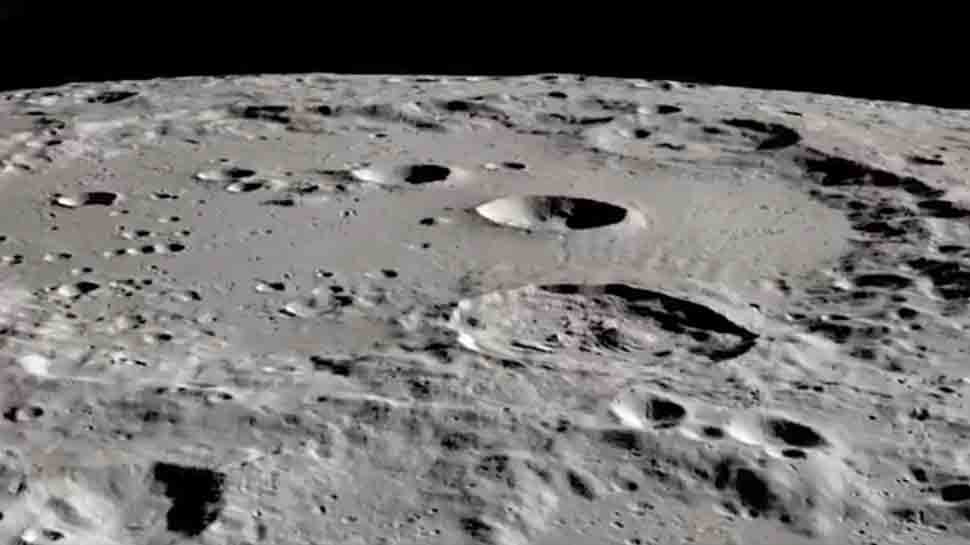

The Moon contains ice water, according to new unequivocal detection data, and on its surface there are numerous craters, even very small, to which sunlight never reaches, where it could be trapped in a stable way, which may have implications for future human missions.

Nature Astronomy publishes on Monday two studies signed by American scientists, one of which points to the unequivocal detection of molecular water (H20) on the Moon and the other suggests that approximately 40,000 square meters of its surface, of which 40% are in the south has the ability to retain water in so-called cold traps.

Two years ago, signs of hydration had already been detected on the lunar surface, particularly around the South Pole, which possibly corresponded to the presence of water, but the method used could not differentiate whether it was molecular water (H2O) or hydroxyl ( radicals called OH).

In this new publication, a team led by Casey Honniball of the University of Hawaii, used data from NASA’s Stratospheric Observatory for Infrared Astronomy (SOFIA), a Boeing 747SP aircraft modified to carry a reflecting telescope.

The data was taken from the Clavius crater, near the South Pole, which was observed by SOFIA at a wavelength of six microns, at which molecular water produces a unique spectral signature.

Previous observations, at a length of three microns, indicated signs of water, which “still left an alternative explanation open,” but the new data “have no other explanation than the presence of molecular water,” astrophysicist Ignasi Ribas told Efe. of the Institute of Space Studies of Catalonia (IEEC) and of the Institute of Space Sciences of the CSIC.

Water, trapped inside grains of dust or crystals, when excited by sunlight vibrates and emits it again at a wavelength of six microns.

“In practice, it is as if those areas of the Moon are brighter than they should at that wavelength,” adds Ribas, commenting on the article of which he is not a signatory.

Researchers estimate that the abundance in high southern latitudes is 100 to 400 grams of H2O per ton of regolith (the material from which the lunar surface is made) and the distribution of water in that small latitude range is the result of geology. local and “probably not a global phenomenon”.

This amount of water is much less than on Earth, “but it is more than zero,” says Ribas, who recalls that conditions on the Moon are extreme, so it is difficult to retain it as it evaporates and escapes.

The second study, led by Paul Hayne of the University of Colorado Boulder, examined the distribution on the lunar surface of zones in a state of eternal darkness, in which ice could be captured and remain stable.

“In cold traps the temperatures are so low that the ice would behave like a rock”, if the water enters there “it will not go anywhere for a billion years”, says the scientist quoted by the university.

Although it cannot be proven that these cold traps actually contain ice reserves – “the only way to do it would be to go there in person or with rovers and dig,” says Hayne – the results “are promising” and future missions could shed even more light. on the water resources of the Moon.

The study was done with data from NASA’s Lunar Reconnaissance Orbiter to evaluate a range of possible cold trap sizes, which may be much more common on the Moon’s surface than suggested in previous research.

Reconnaissance Orbiter

The study was done with data from NASA’s Lunar Reconnaissance Orbiter to evaluate a range of possible cold trap sizes, which may be much more common on the Moon’s surface than suggested in previous research.

The team also used mathematical tools to recreate what the lunar surface might look like on a very small scale, and the answer is that it would be “a bit like a golf ball,” crammed with tiny holes.

The authors suggest that roughly 40,000 square meters of the lunar surface has the ability to trap water, the presence of which may have implications for future lunar missions targeting access to these potential ice reservoirs.

“If we are right,” Hayne considered, “the water will be more accessible,” bearing in mind, in the future, the possible establishment of lunar bases.

The existence of potentially usable water on the Moon is a “very interesting” and “exciting” prospect, Ribas points out, although time will tell if it can be used to help future lunar bases.